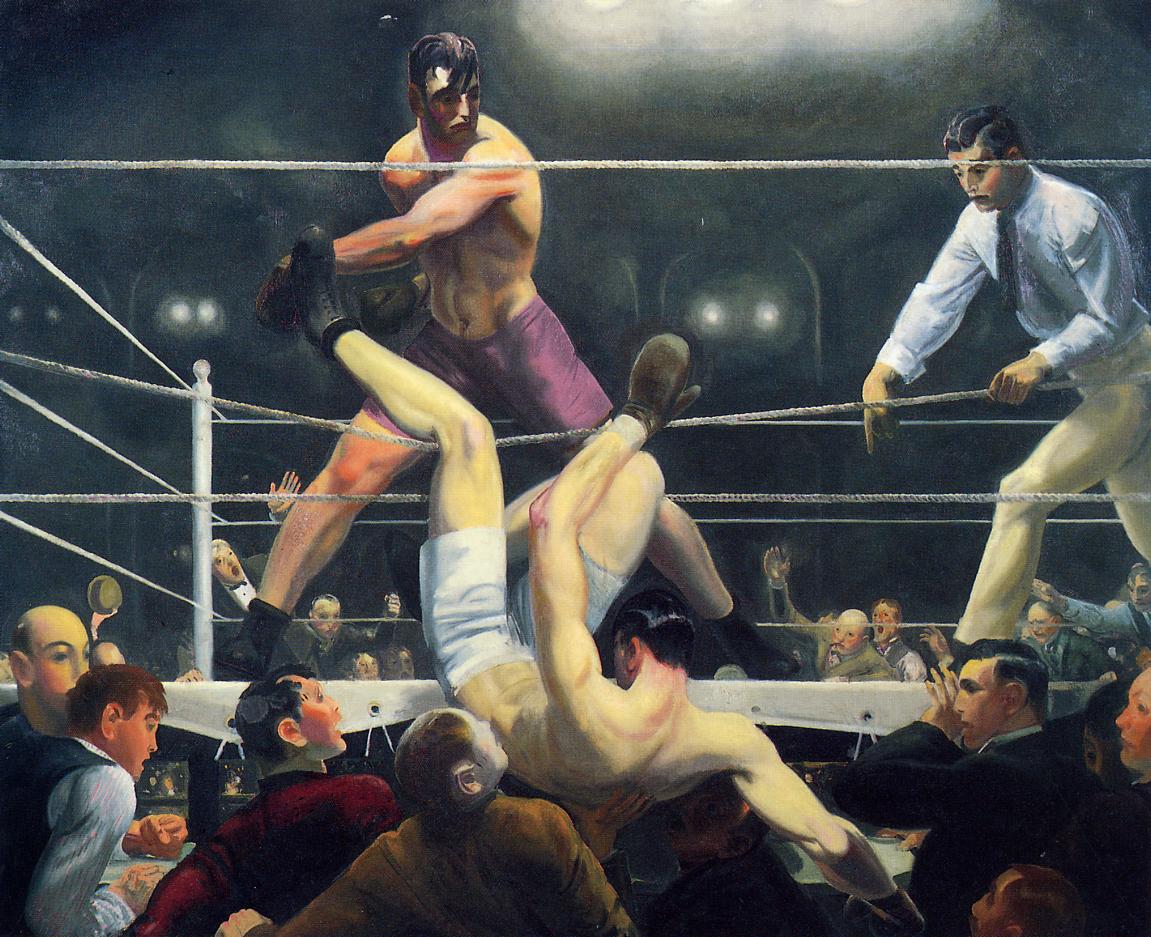

George Bellow’s painting of Dempsey throwing a knockout punch at Firpo (1924)

Recently watching the idiotic debt ceiling debates and the appalling spectacle of the politicians talking over each other, I kept thinking about the culture of language and the idea of populism. How did the idea of Populism, the idea that the decisions should be driven by the people, a fundamental idea to democracy become so corrupted by negative associations? When did the populism become the lowest common denominator? By coincidence, (or maybe it is the temperature of the time), I read an interesting article on populism in Le Monde (in Les débat section) called “Le peuple a-t-il un avenir (Do the people have a future)?” I found one of the articles in this section particularly interesting and relevant in my field, the art.

In “Culture populaire et culture des élite, l’alliance ou la mort (Popular culture and elite culture, the alliance or the death),” Marin de Viry argues that the French society can no longer communicate in a common language because of the wide cultural divide. He suggests that the French people, as a matter of fact, speak 4 different languages: first, the language of an economic elite, who got an MBA from Harvard and works for a global company, and who only have contempt for French culture and wouldn’t care less about Proust; second, the traditional cultural elites, who want to resuscitate the glory days of past French culture, however moth bitten it is; third, what I would translate as tribalists like les bobos (les bourgeois-bohème, somewhat analogous to perhaps hipsters here in America), who are only interested in embellishing and promoting their own tribal cultures (already the readers of Libération and Le Monde speak completely different French); finally, what de Viry calls “the pure victims,” who are indiscriminate, passive consumers of mass produced and artificially manufactured “culture.” The inability to communicate between these 4 groups will eventually create a society and culture that can no longer hold together, which exacerbates political and social problems. He proposes a new conceptual populism that can overcome this isolation using the metaphor of a cross (more of a framework for ideas rather than a concrete suggestion). In the vertical axis, the new language of populism will incorporate as wide time spectrum of the past and the future, and in the horizontal axis, as much of the contemporary society as possible.

This article made me think about the deep political divide between the left and the right in America, and how seemingly they speak only their own tribal languages completely devoid of the base in reality (listen to 3 minutes of Michelle Bachman or Sarah Palin to see the point). But it also made me think about the language and culture gap in the art world itself: how the art world has lost the common language with the different groups in the society resulting in the vanishment of integrated and profound visual culture; how the artists can only talk to the other artists in their own narrow field but not to the public in general or even to other artists or curators in a different field; how some art critiques and some public are only interested in nostalgia of good old days of Titian, Velasquez, Picasso, Cezanne, etc. The worst is that the public, in general, can no longer understand the meaning of contemporary art and alienated from this rich cultural dialog, which in turn alienates and isolates the artists, who now only have the commercial and mercantile relationships with the hedge fund billionaires (so to speak), who are only interested in art as an investment. The state more and more withdraws support from the art as art is no longer perceived to serve any public good.

Populism in the art world itself on the surface seem thriving as the museums are popular than ever, filled with the public. But here also, populism seem to denote the least common denominator, pandering kind of populism, or emphasis on certain kind of tribalism (such as Thomas Hart Benton’s Regionalism or Ashcan School, which understandably was a counter movement to the prevailing trend), not the kind that incorporates the broadest spectrum (including the most challenging parts). In other words, the museums are mounting only certain kind of contemporary art: rather than thoughtful and difficult work, the museums and art institutions prefer a disneyfied spectacle, the bigger and noisier, the better. So what is the solution? Where does the dialog begin? Is is hopelessly late? Or the illusion of one culture itself a pastiche of the past and the vestige of a patriarchal society? At least, artists ourselves should become more aware of our of tribalism and take more initiative in creating dialog with the public. At least, that might help our own sanity.

Kira Nam Greene’s work explores female sexuality, desire and control through figure and food still-life paintings, surrounded by complex patterns. Imbuing the feminist legacies of Pattern and Decoration Movement with transnational, multicultural motifs, Greene creates colorful paintings that are unique combinations of realism and abstraction, employing diverse media such as oil, acrylic, gouache, watercolor and colored pencil. Combining Pop Art tropes and transnationalism, she also examines the politics of food through the depiction of brand name food products, or junk food. Recently, Greene started a figurative painting series spurred by the 2016 Presidential Election, Women’s March, #metoo movement and ensuing crisis of conscience, this new body of work aspires to present the power of collective action by women.

Kira Nam Greene’s work explores female sexuality, desire and control through figure and food still-life paintings, surrounded by complex patterns. Imbuing the feminist legacies of Pattern and Decoration Movement with transnational, multicultural motifs, Greene creates colorful paintings that are unique combinations of realism and abstraction, employing diverse media such as oil, acrylic, gouache, watercolor and colored pencil. Combining Pop Art tropes and transnationalism, she also examines the politics of food through the depiction of brand name food products, or junk food. Recently, Greene started a figurative painting series spurred by the 2016 Presidential Election, Women’s March, #metoo movement and ensuing crisis of conscience, this new body of work aspires to present the power of collective action by women.