I went to Paris in late September and had a marvelous time seeing many interesting shows in galleries and museums as well as hanging out with friends and enjoying wonderful food. This is the first of some blog posts dedicated to the exhibitions that I have seen in Paris.

I was excited to see Masculin/Masculin: L’homme nu dans l’art de 1800 à nos jours at Musée D’Orsay. Unlike the female nude, prevalent in all periods of art history and presented often in major museum, the exhibition focused on the male nude has never been presented in a major institution until the show at the Leopold Museum in Vienna in 2012 (Nackte Männer). Based on this initial show, Musée D’Orsay mounted Masculin/Masculin, drawing from its own vast collection and other French public collections, exploring all aspects of the male nude in art through two centuries down to the present day (and in many different media, including painting, drawing, sculpture and video). The curators divide the exhibition thematically rather than chronologically, bringing interesting dialog across the history in some cases (Photo 1), but also somewhat confusing the changing attitude toward the male nude, which this exhibition aims to catalog (the thematic progression somewhat parallels this approach).

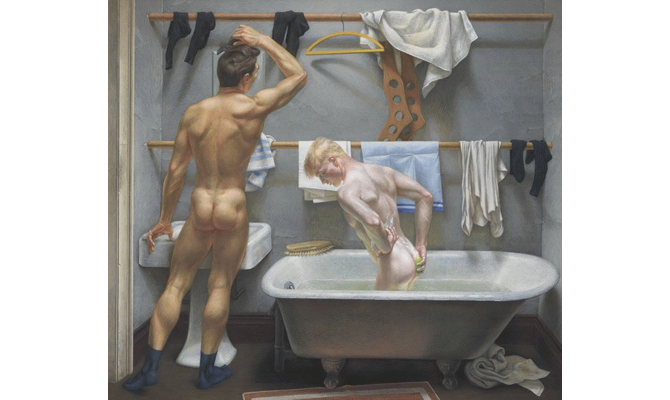

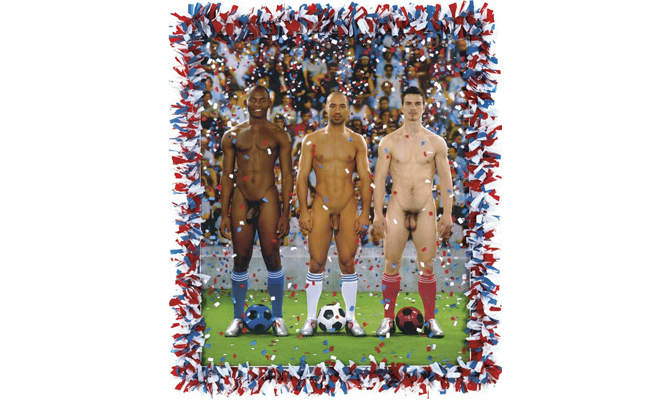

According to the curators, the supremacy of the female nude in art history is essentially a 19th century legacy, establishing it as an absolute and accepted object of male desire. Prior to this, many male artists regarded the male nude as more universal being of “Mankind” representing the “ideal me” of the artists. This view is presented in the first section of the exhibition (L’idéal classique or The Classic Ideal) with the beautiful painting by Jacques Louis David (Photo 2) of a man turned away only presenting his backside. Subsequent sections present the male nude in the themes of Le nu héroique (the Heroic Nude), Les Dieux du stade (the Gods of the Stadium), Dur d’être un héros (It’s tough being a hero), Nuda Veritas, Sans complaisance (Without Compromise), Im Natur, Dans la douleur (In pain), Le Corps glorieux (The Glorious Body), La Tentation du mâle (The Temptation of the Male) and finally L’Objet du désir (The Object of Desire). These thematic progressions more or less correspond chronological evolution in the perception of the male nude even though works from different eras are included in each sections. In the 19th century, artists presented the male nude only in scientific realism or in communion with nature (Photo 4). One of the striking things about this exhibition is the lack of blockbuster names (other than Jacques Louis David and perhaps Gustave Moreau) in 19th century selections in contrast to familiar roster of contemporary artists (the usual suspects includes Paul Cadmus, Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Pierre et Gilles, Ron Mueck and Kehinde Wiley, one of whose painting included is not exactly a male nude painting). Perhaps the bias was the heavy reliance on French collections, but I wish the curators included Kurt Kauper‘s multi-layered male nude paintings of Cary Grant and hockey players. For the curators, limiting the eroticism and desire into last two sections was justified as only the sexual liberation of the 20th century endowed the male body with a sexual charge with the display of more overt homosexual desires.

However, the curators never directly deal with the omnipresent subtext of the sexual tension in the male nude. Unlike the obvious power relationship represented by the objectified female nude, the male nude refuses to engage the public in the same dynamic. Unlike smiling invitation of the full-frontal female nude, most male nude in this exhibition is depicted with 3/4 or fully turned profile with downcast or closed eyes. Only exceptions are bodies depicted in horror or agony. In so many of the paintings, “penis” is the source of great consternation, often shrunken or hidden beneath strategically placed drapery, thong or scabbard (See Jean-Baptiste Frédéric Desmarais’s painting in Photo 1). Often a drawn sword plays a heroic stand-in for the hidden and shrunken male organ with theatrical exaggerations. Even when male sensuality is directly present in the works of many contemporary artists, the desire and eroticism are often cloaked in “campy” theatrical attitude (too many pieces from Pierre et Gilles’ painted photos exacerbate this bias). Given the paucity of any female artists represented in this exhibition, I was left to wonder whether the male nude is ever the fantasy of a heterosexual desires (or objectification).

Kira Nam Greene’s work explores female sexuality, desire and control through figure and food still-life paintings, surrounded by complex patterns. Imbuing the feminist legacies of Pattern and Decoration Movement with transnational, multicultural motifs, Greene creates colorful paintings that are unique combinations of realism and abstraction, employing diverse media such as oil, acrylic, gouache, watercolor and colored pencil. Combining Pop Art tropes and transnationalism, she also examines the politics of food through the depiction of brand name food products, or junk food. Recently, Greene started a figurative painting series spurred by the 2016 Presidential Election, Women’s March, #metoo movement and ensuing crisis of conscience, this new body of work aspires to present the power of collective action by women.

Kira Nam Greene’s work explores female sexuality, desire and control through figure and food still-life paintings, surrounded by complex patterns. Imbuing the feminist legacies of Pattern and Decoration Movement with transnational, multicultural motifs, Greene creates colorful paintings that are unique combinations of realism and abstraction, employing diverse media such as oil, acrylic, gouache, watercolor and colored pencil. Combining Pop Art tropes and transnationalism, she also examines the politics of food through the depiction of brand name food products, or junk food. Recently, Greene started a figurative painting series spurred by the 2016 Presidential Election, Women’s March, #metoo movement and ensuing crisis of conscience, this new body of work aspires to present the power of collective action by women.