My sketch from the exhibition: notation of composition and my deciphering of colors used in the painting. ©Kira Greene

For many art lovers, Henri Matisse (1869–1954) embodies the ease and the elegance of the practice of painting; the beauty of a women’s face depicted with a few strokes of pencil lines; graphic, colorful interiors exuding joie de vivre. The critic Clement Greenberg, writing in The Nation in 1949, called Matisse a “self-assured master who can no more help painting well than breathing.” In contrast to this popular belief, the new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Matisse: In Search of True Painting presents Matisse as the deliberate, thoughtful, even plodding painter, who questioned, repainted, and reevaluated his work constantly. The exhibition shows forty-nine vibrantly colored canvases with the same subject matter in pairs, trios, and series. With repeated observations and compositions,Matisse not only strives to “push further and deeper into true painting” but also struggles to construct an “ideal” or an essence of things, and by extension, his existence: in other words, profound metaphysical exercise with the paint. In this regard, I think that this exhibition would be singularly illuminating metaphysical exercise for practicing artists, especially painters.

Two paintings of Notre-Dame from 1914 are dramatic illustrations of this thought process and practice: one from Kunstmuseum Solothurn, a fairly realistic, fauvist landscape and the other from the Museum of Modern Art, an elegant essence of the building expressed in somber, almost monochrome (with the exception of a glowing green blob of a tree). It’s as if Matisse has peeled away all the extraneous elements of the painting and boiled it down to the most basic elements of composition and color. There are numerous examples of this kind of distillation and contemplation throughout the exhibition: views of interiors with the slightest shifts in perspectives, different views gold fish in a bowl, same men and women painted over and over in different styles.

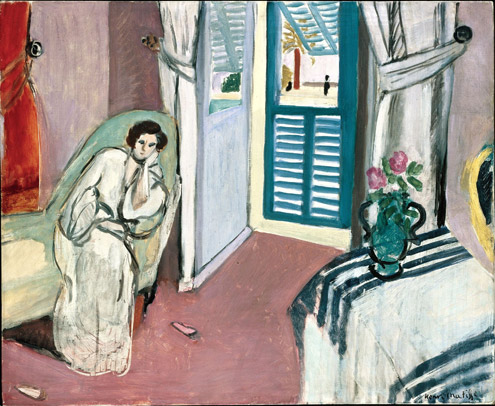

Matisse, Woman on a Divan (Room at the Hôtel Mèditeranée), 1920-21, Kunstmuseum Basel

Going against another popular myth (colorful, happy paintings), I was also struck by overwhelming pathos in Matisse’s paintings. In Woman on a Divan (Room at the Hôtel Mèditeranée), a graceful woman lounges languidly on a green divan in a hotel room filled with bright Mediterranean light. Her languidness is heightened by her voluminous white robe and heavy white curtains pulled back with heavy brass knobs. Beyond the half-closed shutters is pale palm tree and dark silhouettes of figures. Even though the room is filed with cheerful-seeming yellow light and luxurious linens and furnishings, the room is permeated with a certain melancholy and loneliness. Two tiny slippers abandoned on the mauve-pink floor and almost painted over with the same color. The same mauve is also used in hastily sketched vase of flowers. These objects emanate almost unbearable melancholia. For Matisse, life, at first glance, is a joy surrounded by domestic comfort but when stripped bare, nothing but an elegant pathos of loneliness. Perhaps a sentiment particularly domestic, particularly French and particularly of Matisse’s time and class.

Kira Nam Greene’s work explores female sexuality, desire and control through figure and food still-life paintings, surrounded by complex patterns. Imbuing the feminist legacies of Pattern and Decoration Movement with transnational, multicultural motifs, Greene creates colorful paintings that are unique combinations of realism and abstraction, employing diverse media such as oil, acrylic, gouache, watercolor and colored pencil. Combining Pop Art tropes and transnationalism, she also examines the politics of food through the depiction of brand name food products, or junk food. Recently, Greene started a figurative painting series spurred by the 2016 Presidential Election, Women’s March, #metoo movement and ensuing crisis of conscience, this new body of work aspires to present the power of collective action by women.

Kira Nam Greene’s work explores female sexuality, desire and control through figure and food still-life paintings, surrounded by complex patterns. Imbuing the feminist legacies of Pattern and Decoration Movement with transnational, multicultural motifs, Greene creates colorful paintings that are unique combinations of realism and abstraction, employing diverse media such as oil, acrylic, gouache, watercolor and colored pencil. Combining Pop Art tropes and transnationalism, she also examines the politics of food through the depiction of brand name food products, or junk food. Recently, Greene started a figurative painting series spurred by the 2016 Presidential Election, Women’s March, #metoo movement and ensuing crisis of conscience, this new body of work aspires to present the power of collective action by women.